Two Markets, One Narrative, and a Structural Mismatch

Why Mainland A-Shares, Hong Kong or “Greater China” Behave Like Separate Asset Classes? Where Alpha Actually Exists? How to Extract That Alpha?

Foreword from Alpha Talon

This piece is a direct follow-up to our earlier analysis, “The Mirage of Cheapness”, linked here:

We strongly recommend reading that article first. It lays the necessary foundation for understanding how China’s equity markets function, why “cheap” is often a misleading signal, and where many investors go wrong at the structural level.

In this follow-up, we go deeper. The goal here is not to rehash macro headlines or recycle valuation arguments, but to dissect China and its subsidiary markets, most notably Hong Kong, as distinct but interconnected systems. We focus on how capital actually moves, how policy interacts with market structure, and why economic growth so often fails to translate into durable equity returns for long-term investors.

This is an analytical and commentary-driven piece. We examine the mechanical links between mainland China and Hong Kong, the limits of those linkages, and the behavioral and institutional dynamics that shape outcomes in practice. If the first article explained why China appears cheap, this one explains why that cheapness persists and under what conditions, if any, alpha can realistically be extracted.

As always, our intent is clarity over comfort. China is not a single market, and treating it as one is the fastest way to misprice risk.

Two Markets with Different But Shared DNA: The Tale of A and H

Mainland China’s A-share markets in Shanghai and Shenzhen operate under a rulebook that is fundamentally orthogonal to what global investors recognize as a modern, liberalized equity market. These are tightly controlled capital markets where regulatory design is not incidental but intentional, embedding policy objectives directly into market mechanics. Daily price limits (typically ±10%, extended to ±20% for STAR and ChiNext boards), a T+1 trading regime (do not confuse with T+1 settlement system) that prohibits same-day selling, and episodic regulatory intervention collectively shape not only volatility profiles but investor behavior itself. Price discovery is filtered, delayed, and at times explicitly managed. Stability and control are prioritized over efficiency.

Governance and disclosure standards further reinforce this dynamic. Regulatory discretion in enforcement, frequent shifts in policy emphasis, and uneven application of rules introduce an additional layer of uncertainty that investors must continuously price. In this environment, valuation is rarely a clean function of fundamentals alone; it is an output of policy expectations, liquidity conditions, and regulatory posture at any given moment. Time horizons compress accordingly.

Historically, A-shares have been dominated by retail participation, which has imparted a distinct behavioral signature on the market. Sharper sentiment swings, momentum-driven rallies, thematic speculation, and persistent valuation anomalies have been the defining features. The shorthand that “China is a retail market” has been broadly accurate for much of the past decade. However, this characterization is becoming incomplete. Institutional participation, particularly from both domestic and global mutual funds, state-aligned capital pools, and policy-directed vehicles has increased meaningfully in recent years. This shift does not eliminate volatility or speculative excess, but it does complicate the flow dynamics. Price action is no longer purely retail-driven; it increasingly reflects a hybrid interaction between sentiment-led retail flows and strategically deployed institutional capital, often with policy objectives rather than return maximization as the primary constraint.

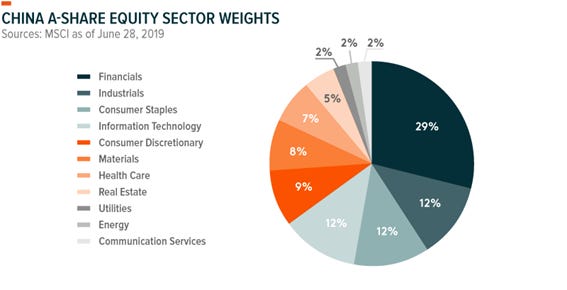

Sector composition reinforces these characteristics. The A-share market is structurally overweight cyclical, capital-intensive, and policy-sensitive sectors such as industrials, materials, financials, and infrastructure-linked enterprises. These businesses are deeply entwined with China’s domestic credit cycle, fiscal stance, and administrative priorities. Earnings visibility is therefore subordinate to macro liquidity, regulatory signals, and shifts in government emphasis. While genuine long-duration growth companies exist within the A-share universe, their equity narratives are frequently overwhelmed by near-term cyclical and policy considerations, limiting their ability to compound valuation multiples over time.

Hong Kong presents a stark contrast. The H-share market (in this case we will be using Hang Seng Index or “HSI”) is an open, internationally integrated financial ecosystem governed by globally familiar standards. Capital moves freely, settlement conventions align with other major financial centers, and disclosure frameworks are broadly legible to global institutions. Liquidity is shaped primarily by international risk appetite, benchmark inclusion, and cross-border capital allocation decisions, rather than domestic policy signaling or retail sentiment cycles. As a result, price formation in Hong Kong more closely resembles that of other developed international markets, even when the underlying issuers are China-centric.

This divergence is most visibly expressed through valuation. The persistent and fluctuating AH premium, where A-shares trade at a premium to economically equivalent H-shares is not a simple arbitrage anomaly. It reflects deep structural differences in investor base, capital mobility, currency convertibility, and perceived risk. Mainland investors, constrained by capital controls and limited access to offshore assets, often bid up domestic listings. Global investors, by contrast, apply a higher discount rate to Chinese risk when expressed through Hong Kong, reflecting regulatory uncertainty, geopolitical considerations, and capital repatriation concerns. The result is a valuation gap that can persist for years and only compress episodically, typically during policy-driven liquidity surges.

Market composition further differentiates the two. Hong Kong’s equity universe is increasingly biased toward sectors with global relevance and comparability: technology platforms, private financial services, consumer franchises, and internationally exposed enterprises. These companies are analyzed and priced through a global lens, benchmarked against international peers, and embedded in global portfolios. Even when revenues are overwhelmingly domestic, the capital pricing them mixed between domestic and global.

The key takeaway is both simple and routinely overlooked: A-shares and H-shares are not the same asset class. Mainland China’s closed capital account, active regulatory overlay, and historically retail-heavy participation create market behaviors and valuation dynamics that are fundamentally distinct from Hong Kong’s open, institutionally dominated, globally priced environment. Treating them as interchangeable expressions of “China exposure” is not merely imprecise — it is a structural error that leads to flawed Emerging Market (EM) portfolio construction, mismatched time horizons, and misplaced expectations of return.

For investors seeking durable outcomes, recognizing and respecting this duality is not optional. It is the starting point.

The SH–SZ–HK Connect: A Framework, Not Full Integration

The Shanghai–Hong Kong and Shenzhen–Hong Kong Stock Connect programs are frequently portrayed as a structural unification of China’s onshore and offshore equity markets. This interpretation is convenient, but fundamentally flawed. Stock Connect is not market integration; it is a quota-based access framework designed to facilitate incremental cross-border participation without surrendering control over capital flows, market rules, or regulatory sovereignty. It opens a door, but keeps the room partitioned.

At its core, Stock Connect functions as a controlled conduit. Eligible investors may access a defined universe of securities across borders, but only within daily and aggregate quota limits, eligibility screens, and operational constraints determined by regulators on both sides. Capital is permitted to flow, but only at the margin and only under predefined conditions. This design reflects policy intent: improve liquidity and international participation without exposing domestic markets to unfettered capital mobility or regulatory arbitrage.

Critically, Stock Connect does not harmonize trading regimes. Investors remain fully subject to the rules of the market in which the security is listed. Foreign investors buying A-shares through Stock Connect must comply with China’s T+1 trading regime, daily price limits, and trading suspensions. These constraints materially alter execution, risk management, and strategy design. Similarly, mainland investors accessing Hong Kong equities must operate under Hong Kong’s T+2 settlement cycle (Hong Kong is moving towards a T+1/0 settlement cycle), disclosure standards, and market practices. These are not administrative footnotes; they directly affect turnover, volatility, liquidity provisioning, and the feasibility of certain trading strategies.

As a result, Stock Connect leaves intact the deeper structural divides that matter most to long-term investors. Corporate governance frameworks, accounting standards, enforcement credibility, currency convertibility, dividend repatriation, and listing requirements remain fundamentally different across the two markets. These elements define risk premia and valuation durability. Stock Connect does not converge them. It improves access, not alignment.

Since the launch of Stock Connect, liquidity has improved in select names, particularly large-cap dual-listed companies. Short-term price discovery has also become more efficient at the margin. However, the convergence stops there. Academic and market studies consistently show only partial and episodic co-movement between A-shares and their H-share equivalents. Correlations tend to rise during periods of strong southbound or northbound flows, policy easing cycles, or speculative rallies. Just as consistently, they deteriorate when liquidity tightens, sentiment shifts, or regulatory constraints reassert themselves. This pattern reflects conditional convergence, not structural integration.

From an asset-allocation perspective, this distinction is decisive. A fully integrated market would imply stable arbitrage, converging valuation multiples, and aligned risk pricing across listings. That is not what Stock Connect delivers. Instead, it produces intermittent linkages layered on top of structurally distinct systems. Investors who mistake access for integration often underestimate basis risk, overstate diversification benefits, and misprice drawdown scenarios.

The correct interpretation is therefore pragmatic: Stock Connect is a set of narrow capital channels, not a unified marketplace. It facilitates participation without dissolving the institutional, regulatory, and capital-account barriers that define how China and Hong Kong equities trade and compound capital. Viewing Stock Connect as proof that “China is becoming one market” is a category error and one that has repeatedly led global investors to misjudge both opportunity and risk.

China’s Economic Growth Reality vs. Market Expectations

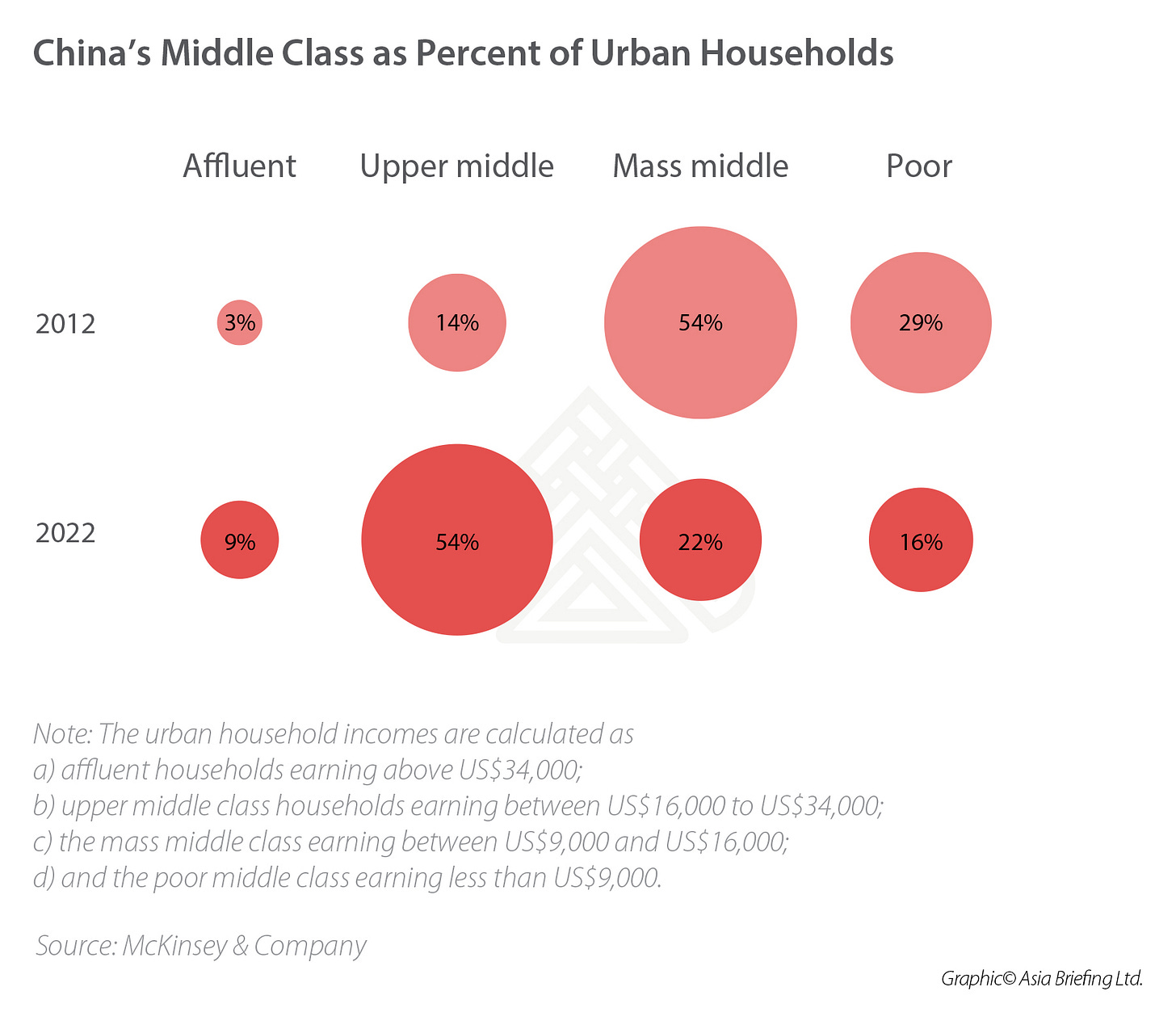

For two decades, the China bull case was a clean story: rapid modernization, a exponentially rising middle class, and an innovation flywheel that would eventually compound into durable equity returns. That story wasn’t “wrong”, but it was linear and China’s reality is not. The economic engine is still large and capable of producing headline growth, but the composition of that growth has shifted and the confidence behind it has deteriorated.

The IMF’s latest baseline still shows meaningful GDP expansion (mid-single digits in 2025, stepping down in 2026), but it explicitly flags the same core problem investors keep running into: domestic demand remains persistently weak, and the property sector is still not on solid footing, which drags confidence and keeps the economy leaning too hard on exports.

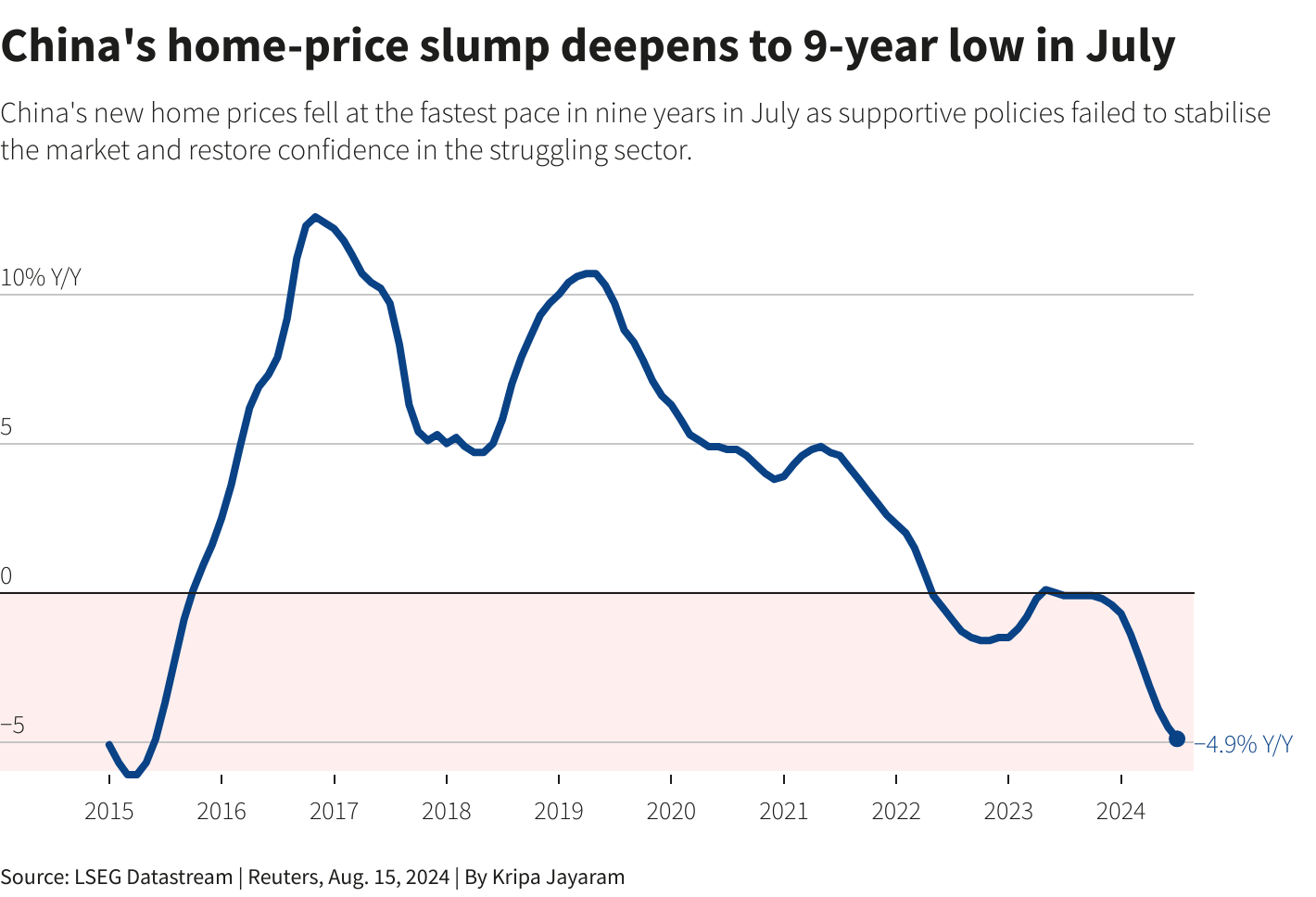

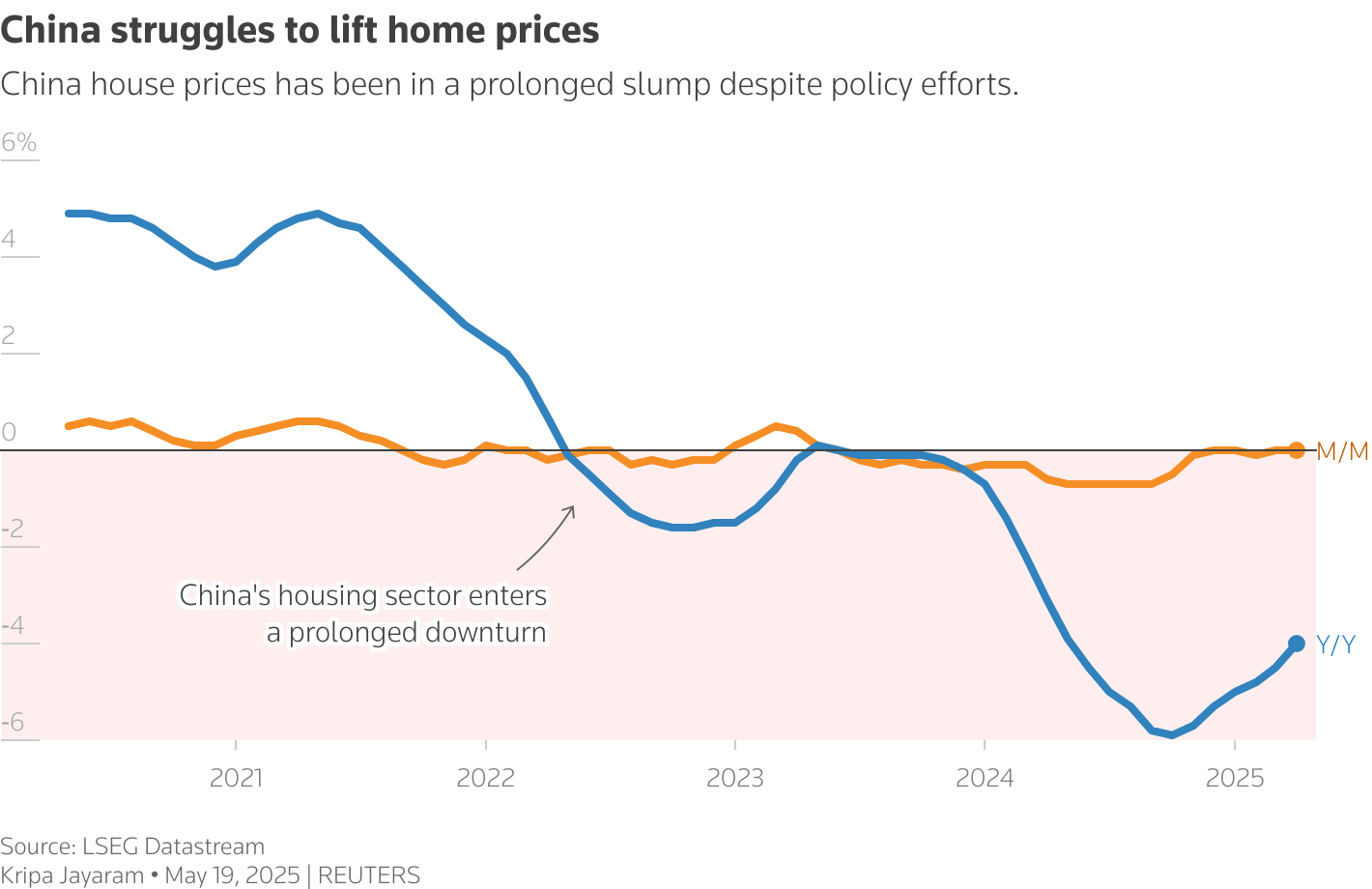

As we have previously discussed the property drag is not a talking point; it is a structural weight on household balance sheets, local government finances, and consumer psychology. All reporting continues to show ongoing home price weakness into late-2025, reinforcing the idea that “stabilization” is a slow grind rather than a clean inflection. The World Bank’s China Economic Update frames this as a prolonged adjustment that can hinder any strong rebound, even when policy leans supportive. When your largest store of household wealth is under pressure, you don’t get aggressive discretionary consumption; you get caution, savings, and “wait and see”.

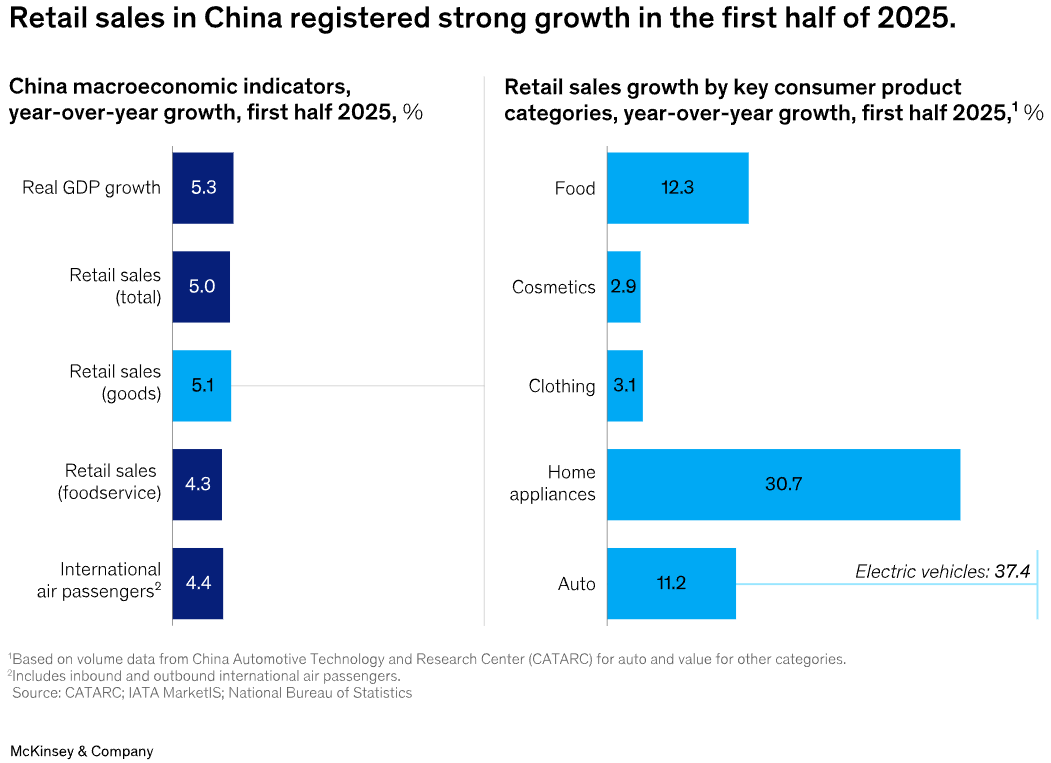

That’s why you see the weird macro optics investors outside China often misread: high savings co-existing with subdued spending. This isn’t a liquidity problem; it’s expectations. McKinsey’s consumer work in 2025 highlights how the consumer outlook remains cautious, with modest expected consumption growth, consistent with a society prioritizing savings and defensiveness over exuberance. And IMF commentary reinforces the mechanism: shaky property footing depresses confidence, which depresses consumption and contributes to disinflationary pressure. In short: the household is acting rationally given uncertainty, even if policymakers would prefer a demand stabilization and subsequent boom.

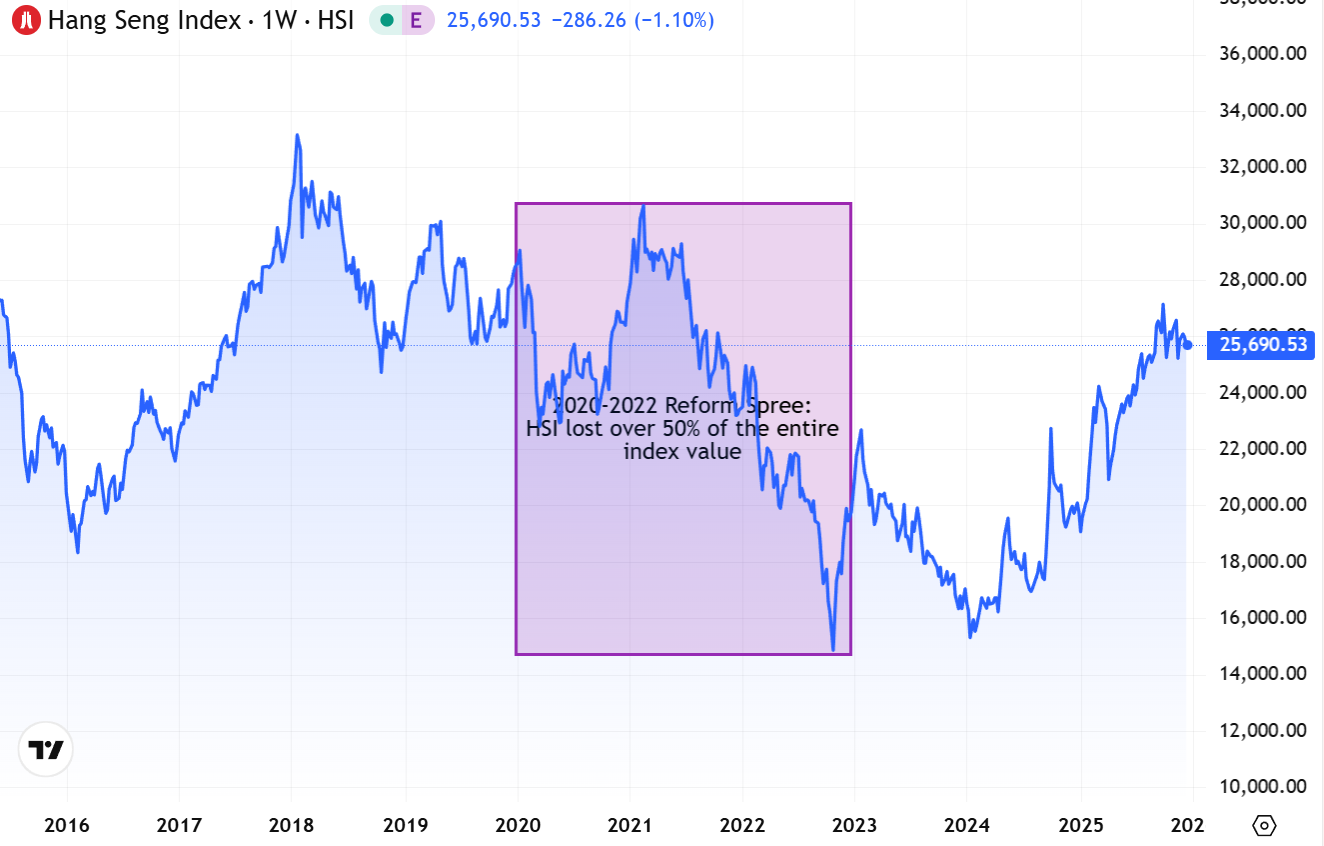

Now layer on the second reality: macro policy intervention is frequent, and it is not always optimized for equity-market stability or minority shareholder outcomes. China can move fast, sometimes impressively too fast, but that speed cuts both ways. Sector incentives can change abruptly when political priorities shift (industrial policy, “common prosperity”, data security, platform regulation). The 2020-2022 platform regulatory transition is a clean example of how quickly the regime can re-price an entire profit pool, and why long-duration cash-flow assumptions get discounted. This creates what we think is the most underappreciated “China discount” driver: investors don’t just price earnings, they price governance regime volatility applied to earnings.

So the “market disconnect” isn’t mysterious. China’s growth doesn’t mechanically translate into stock returns because the equity market is not a simple GDP tracker. Returns are a function of capturability (can shareholders actually keep the economics?), predictability (can the rules of the game be modeled with confidence?), and capital channel behavior (do domestic and global pools allocate for duration or for tactical windows?). When regulatory and policy uncertainty compress duration, we end up with a market that can look statistically cheap, sometimes very cheap, yet still fail to deliver the long-term compounding or short-term re-rating that global investors expect.

That’s the punchline: China often “feels” cheap because the multiples are cheap, but the market is implicitly telling you why, you’re not buying a stable long-duration cash-flow stream; you’re buying exposure to an evolving policy regime. And unless policy execution aligns cleanly with a confidence-driven domestic demand recovery (not just export strength), the path from macro growth to shareholder compounding will remain uneven and frequently frustrating.

China’s Economic Growth Reality vs. Market Expectations

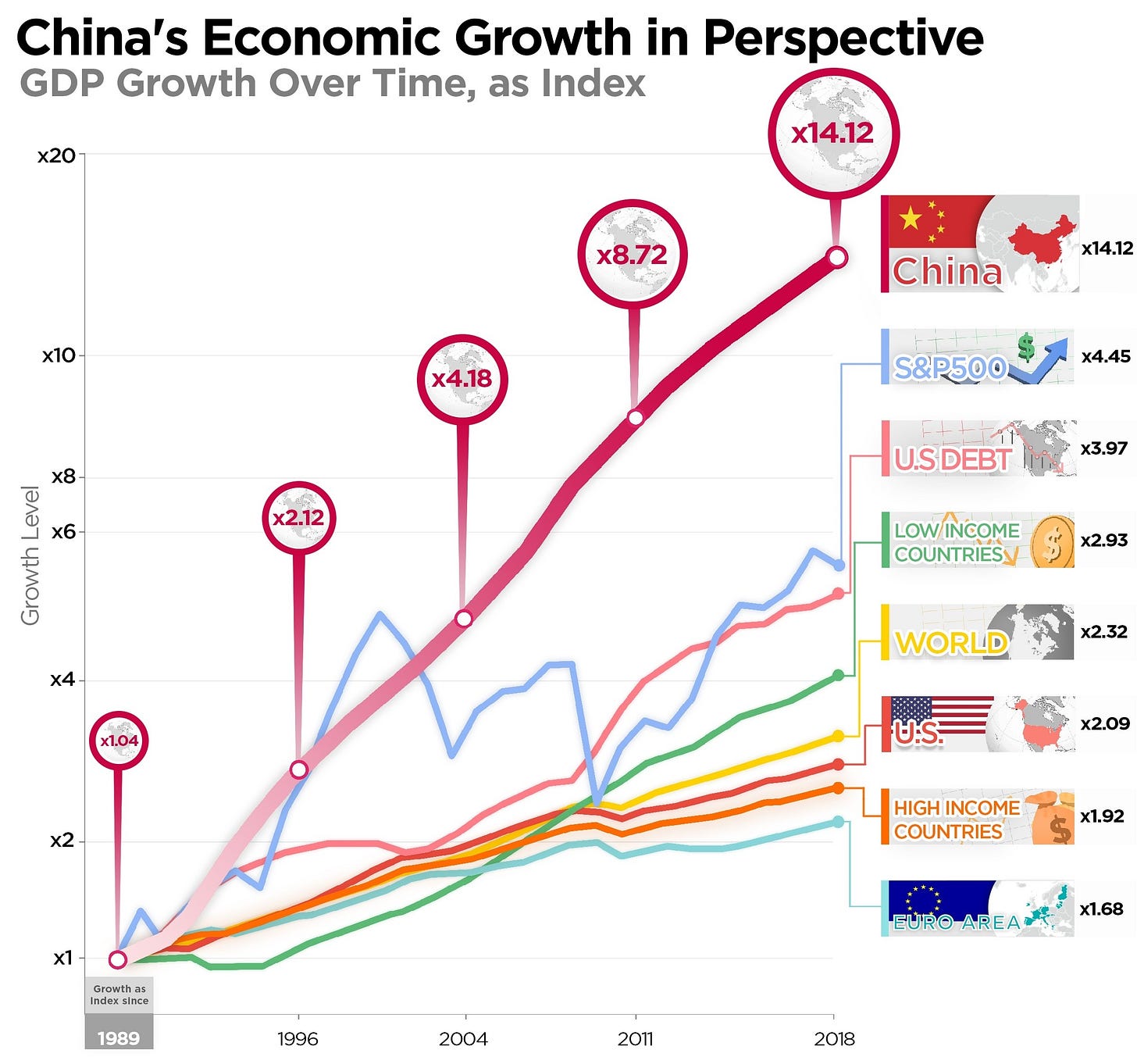

For much of the past two decades, the China bull case rested on a deceptively clean narrative arc: rapid urbanization, an ever-expanding middle class with no end insight, and an innovation flywheel that would eventually translate scale into durable equity compounding through overall economic growth. That narrative was not incorrect, but it was linear, and China’s economic evolution has proven anything but. The economy remains large, complex, and capable of producing headline growth, yet the quality, composition, and confidence behind that growth have changed in ways that materially weaken its transmission into equity returns (maybe for a different analysis, the above applies more towards Chinese wage equality growth).

At the macro level, China is still growing. The IMF’s latest baseline projections point to mid-single-digit GDP expansion in 2025, moderating further into 2026. On paper, those numbers would ordinarily be supportive of equity multiples. However, the same forecasts repeatedly emphasize a persistent internal imbalance: domestic demand remains structurally weak, household confidence subdued, and the property sector crisis unresolved. As a result, growth continues to lean disproportionately on exports and state-directed investment rather than on self-sustaining private consumption. This is not the growth mix that historically generates durable equity re-ratings.

The property sector is central to this disconnect and cannot be dismissed as a cyclical drag or temporary adjustment. Residential real estate has functioned as the primary store of household wealth, a key collateral base for credit creation, and a major revenue source for local governments. Ongoing home price weakness into late-2025, confirmed across multiple data sources, continues to weigh on all three. Stabilization, where it exists, is incremental and uneven, not the kind of decisive inflection that resets confidence. The World Bank has framed this adjustment as prolonged and structurally constraining, even in the presence of policy support. When the dominant household asset class is under pressure, the behavioral response is predictable: precautionary saving rises, discretionary consumption falls, and economic optimism erodes.

This explains a pattern that external observers often misinterpret. China today exhibits high household savings alongside weak consumption growth, a combination that appears contradictory only if one assumes liquidity constraints are the binding factor. They are not. This is an expectations problem, not a cash problem. Households are acting rationally in the face of uncertainty around asset values, employment stability, and policy direction. McKinsey’s 2025 consumer research reinforces this point, highlighting a persistently cautious outlook and only modest expected consumption growth, even as balance sheets remain relatively liquid. IMF analysis echoes the same mechanism: property-driven confidence shocks feed directly into subdued demand and disinflationary pressure.

Layered on top of this is China’s policy reality. Macro and regulatory intervention is frequent, often decisive, and not primarily optimized for equity market stability or minority shareholder outcomes. The state retains broad discretion to reallocate economic rents in pursuit of social, political, or strategic objectives. That discretion is a feature, not a bug, of the system. While this capacity allows for rapid mobilization and targeted support, it also introduces a form of governance regime volatility that is difficult to model and easy to underestimate.

The 2020-2022 platform regulation cycle or “2020–2021 Xi Jinping Administration reform spree” remains the clearest modern example. Entire profit pools were re-priced in a short period, not because of deteriorating unit economics, but because policy priorities shifted. The lesson global investors absorbed was not simply that regulation can happen; it was that the timing, scope, and duration of regulatory regimes are inherently uncertain. That uncertainty compresses valuation duration. Investors do not just discount earnings; they discount the stability of the rules under which those earnings are generated.

This dynamic is, in our view, the most underappreciated driver of China’s persistent valuation discount. Markets are not rejecting growth; they are questioning capturability and predictability. Equity returns require confidence that future cash flows will accrue to shareholders under a reasonably stable governance framework. When policy discretion is broad and the signaling horizon is short, long-duration cash flows are discounted aggressively, regardless of near-term growth rates.

As a result, the “market disconnect” that frustrates global allocators is not mysterious. China’s equity market is not a GDP tracker. Returns are a function of three variables that are often misaligned in China:

Capturability: whether shareholders can reliably retain economic value.

Predictability: whether policy, regulation, and enforcement can be modeled with confidence.

Capital behavior: whether domestic and global capital allocates for duration or merely trades tactical windows.

When these variables compress duration, equities can appear statistically cheap, sometimes extremely cheap without delivering either sustained compounding or meaningful re-rating. Multiples are not “wrong”; they are expressive. They reflect a rational market response to uncertainty around confidence, governance, and demand transmission.

That is the core punchline. China often feels cheap because the numbers are cheap. But the market is signaling that investors are not buying a stable, long-duration cash-flow stream. They are buying exposure to an evolving policy regime layered on top of a cautious domestic demand base. Unless policy execution aligns credibly with a confidence-driven recovery in household behavior, not merely export strength or episodic stimulus, the translation from macro growth to shareholder compounding will remain uneven, episodic, and frequently frustrating.

Transmission to Greater China: Why Hong Kong Prices China’s Reality More Harshly

The structural realities of China’s growth model do not stop at the mainland border; they are most visibly and efficiently priced in Hong Kong. If A-shares often reflect domestic liquidity, sentiment, and policy intent, Hong Kong functions as the external pricing mechanism for China risk. It is where global capital aggregates macro uncertainty, governance risk, and confidence erosion into a single discount rate.

Hong Kong’s equity market sits downstream of China’s growth narrative, but upstream of its policy discretion. As a result, it absorbs the negative externalities of China’s economic transition more directly than mainland markets. Weak domestic demand, unresolved property adjustments, and uncertain policy signaling do not manifest in Hong Kong as cyclical volatility alone; they manifest as duration compression. Global investors shorten their time horizons, reduce terminal value assumptions, and demand higher risk premia for holding Chinese cash flows offshore.

This is why Hong Kong equities often underperform during periods when China’s headline growth remains intact. The issue is not growth per se, but growth quality and confidence. When domestic demand is weak and households remain defensive, Hong Kong-listed companies tied to consumption, platforms, and financial intermediation face persistent skepticism. Export strength may support revenues in certain sectors, but it does little to restore confidence in a self-reinforcing domestic growth loop — the condition required for sustained multiple expansion.

Property weakness is again a critical transmission channel. While Hong Kong is no longer economically dependent on mainland property development, the sector’s role in household wealth and local government finance continues to influence credit creation, bank balance sheets, and consumer behavior across Greater China. Hong Kong-listed banks, insurers, developers, and asset managers are therefore priced with an embedded assumption that balance-sheet repair and confidence rebuilding will be prolonged. Even where direct exposure is manageable, perceived systemic linkage is enough to cap valuations.

Policy uncertainty amplifies this effect. Hong Kong markets price not only current regulation, but the option value of future intervention. The platform regulation cycle of 2020-2022 fundamentally altered how global investors underwrite Chinese equities listed in Hong Kong. Earnings are no longer discounted using conventional sector multiples alone; they are discounted using an additional governance volatility factor. This is why even operationally strong, cash-generative businesses struggle to command global peer multiples. The market is pricing policy convexity, not just business fundamentals.

Importantly, Hong Kong’s investor base makes this discount persistent. Unlike mainland markets, Hong Kong is dominated by institutional capital, global long-only funds, hedge funds, sovereign allocators, and benchmark-constrained investors. These participants are structurally sensitive to drawdown risk, headline volatility, and policy credibility. When confidence erodes, they do not rotate aggressively within the market; they reduce exposure outright. This creates a one-way valve effect: inflows are cautious and incremental, while outflows can be abrupt.

This dynamic explains a recurring pattern in Hong Kong equities: sharp, policy-driven rallies followed by rapid retracement. When Beijing signals support through easing measures, verbal guidance, or sector-specific relief, Hong Kong reacts immediately. Liquidity returns, short covering accelerates, and valuations snap higher. But absent a clear follow-through in domestic demand, property stabilization, and regulatory clarity, these rallies struggle to sustain. The market reverts to pricing China as a trading venue, not a compounding one.

The persistent discount of H-shares relative to both A-shares and global peers is therefore not an anomaly or a failure of investor imagination. It is the rational outcome of Hong Kong’s role as the global clearing price for China risk. Where mainland markets can temporarily insulate prices through policy guidance, liquidity management, or retail participation, Hong Kong cannot. It reflects what global capital is willing to pay for Chinese cash flows given current confidence, governance, and growth transmission.

The implication for investors is straightforward but uncomfortable: Hong Kong does not lag China’s recovery; it waits for proof. Until domestic demand visibly re-anchors growth, property adjustment reaches a credible floor, and policy signaling stabilizes for long enough to restore duration confidence, Hong Kong equities will continue to price China conservatively, even when the macro data appears supportive.

In that sense, Hong Kong is not mispricing China. It is pricing China speculatively and honestly.

The Short-Term, Speculative DNA of Chinese Markets

In mainland China equities, investors are often compensated more quickly for correctly interpreting policy direction, liquidity signals, and crowd psychology than for being right on long-term fundamentals. This is not a critique of market participants; it is a reflection of market design. The A-share market is structurally optimized for policy transmission and sentiment response, not for slow, fundamentals-led compounding. Investors who approach it with developed-market or long-term assumptions tend to experience repeated whipsaws, not due to poor analysis, but because they are applying the wrong framework to the wrong regime.

Price action in A-shares is frequently driven by policy signaling, thematic endorsement, and narrative momentum. Government guidance, whether explicit policy announcements, sector prioritization language, or shifts in enforcement posture, functions as a dominant macro factor. Markets rapidly internalize what is perceived to be “in favor” and crowd into those themes with little regard for near-term valuation constraints. Conversely, when a theme loses policy sponsorship, capital exits just as quickly. In this environment, alpha is often a function of timing and positioning, not intrinsic value realization.

Investor composition reinforces this dynamic. Retail participation remains significant, and retail capital naturally gravitates toward what is visible, interpretable, and immediate. Headlines, slogans, sector narratives, and price momentum matter more than discounted cash flow models. Importantly, this does not imply irrationality. Retail behavior is a rational adaptation to a market where policy and liquidity shocks dominate the short-term payoff function. Institutional capital participates as well, but often tactically, reinforcing momentum rather than countering it.

Market mechanics further amplify reflexivity. The T+1 trading regime, which prohibits same-day selling, compresses decision-making horizons and intensifies behavioral clustering. When sentiment turns, the inability to exit immediately creates “tomorrow risk”, accelerating herding behavior as investors rush to preempt future selling pressure. Daily price limits introduce another distortion. In crowded trades, limits can transform price discovery into a sequence of discrete repricings rather than a continuous process. Momentum becomes stair-stepped, and late entrants risk being trapped at limit-up levels, effectively buying liquidity rather than value.

Short-selling constraints compound these effects. While shorting is permitted in theory, the depth, availability, and participation are materially weaker than in mature Western markets. This reduces two-sided market discipline and allows narratives to overshoot before fundamentals or arbitrage can exert counterpressure. As a result, speculative themes often persist longer than fundamentals would justify, only to unwind sharply once sentiment or policy signals shift.

Sentiment itself is unusually tradable in China. Social platforms, thematic forums, and retail-oriented channels propagate narratives at speed and scale. Social sentiment indicators can correlate with near-term trading volume, volatility, and intraday price behavior in Chinese equities. Whether one views these signals as exploitable alpha or as noise, the implication is clear: the market often moves first and rationalizes later. By the time a fundamental thesis is validated, the trade may already be crowded or unwinding.

The result is a market where short-horizon price action frequently dominates, and fundamentals operate as a second-order driver in the moment. This does not mean fundamentals are irrelevant. Over longer arcs, they still anchor outcomes, but only under specific conditions. Fundamentals tend to assert themselves when the policy regime is stable, liquidity is supportive, and the sector in question is not subject to recurrent regulatory repricing. Outside those windows, valuation can remain latent for extended periods, testing the patience and risk tolerance of long-duration investors.

The uncomfortable but necessary conclusion is that in China A-shares, valuation alone is insufficient. Timing, regime awareness, and liquidity conditions determine whether valuation is rewarded or ignored. The market is not hostile to fundamentals; it is selective about when they matter. Investors who recognize this dynamic can adapt, using fundamentals to define opportunity sets, while using policy and sentiment to define entry, exit, and sizing. Those who do not will continue to confuse structural behavior with market inefficiency.

Retail vs Institutional: Who’s Really Bagholding?

The reductive framing that “retail investors are dumb and institutions always win” is both inaccurate and unhelpful, particularly in China, where market structure and incentive design matter more than investor intelligence. Outcomes are shaped less by who is “right” and more by who is aligned with the market’s dominant payoff function at a given point in the cycle.

Mainland A-share markets have historically been retail-heavy (as high as 90% of trading volume), and that composition undeniably amplifies momentum, narrative-driven trading, and crowded positioning. However, it is a mistake to assume that rallies are merely the product of unsophisticated retail speculation turned into snowball crowding rallies. By 2025, multiple flow analyses and market commentaries indicate that institutional participation has become a primary marginal driver of price action. Domestic mutual funds, insurers, exchange-traded funds (ETFs), and policy-aligned capital have increasingly taken the lead in initiating and sustaining market moves, particularly during policy-supported phases. Retail capital often follows, it does not always originate.

This shift complicates the old narrative. The market is no longer a simple retail casino occasionally interrupted by state intervention. It is better understood as a hybrid system, where institutional capital frequently sets the direction and retail participation amplifies it. When policy guidance is supportive or liquidity conditions improve, institutions can move first, establishing positions that are later reinforced by retail inflows once price action validates the narrative. The resulting momentum can look like retail excess, even when it is institutionally seeded.

Hong Kong, by contrast, operates under a very different equilibrium. It is international by design and institutionally dominated in practice. According to HKEX, institutional investors, both domestic and overseas, account for roughly two-thirds of total market turnover. This composition has direct implications for how risk is priced. Hong Kong equities reflect global capital cycles, dollar liquidity, benchmark positioning, and geopolitical risk, not just local sentiment or policy signaling. As a result, Hong Kong tends to reprice China risk earlier and more decisively than onshore markets, particularly during periods of global risk aversion.

The question of “bagholding” is therefore not about intelligence or financial literacy, but about time horizon and flexibility. Retail investors are not doomed to lose, but the odds deteriorate in markets that structurally reward short-duration positioning. In mainland markets, late-cycle dynamics are often predictable: narratives accelerate, price action confirms the narrative, and retail participation increases as visibility improves. When the regime shifts due to macro shocks, policy disappointment, or liquidity tightening, retail investors are more likely to become forced sellers. This is not because they are uniquely irrational, but because they are typically less able to tolerate drawdowns, less diversified, and more exposed to psychological and financial leverage.

Institutions, meanwhile, do not win by default, but they often control timing. They have the ability to accumulate earlier, size positions dynamically, distribute into strength, and reduce exposure before regime shifts fully manifest in price. Their advantage lies in process rather than prescience: better risk management frameworks, clearer mandates, superior access to liquidity, and the operational capacity to adjust exposure without capitulation. In China’s policy-driven environment, these advantages are magnified. Capital controls, episodic intervention, and abrupt signaling changes compress reaction windows, making timing more valuable than conviction.

This is where the “exit liquidity” framing originates. It is not a claim of malice or manipulation. It is an acknowledgment that institutional capital is structurally positioned to transfer risk, while retail capital often absorbs it late in the cycle. When regimes are stable and fundamentals dominate, this asymmetry narrows. When regimes shift quickly as they frequently do in China,it widens.

The broader implication is uncomfortable but essential: Chinese equity markets, particularly onshore, are environments where timing frequently beats truth. Fundamentals still matter, but they matter unevenly and often on delayed timelines. Investors who recognize this can adapt/aligning their horizon, sizing, and expectations with the market’s structure. Those who do not may find themselves repeatedly “right” on fundamentals, yet consistently on the wrong side of price.

In China, bagholding is not a function of who you are. It is a function of when you show up, how long you stay, and whether your horizon matches the regime.

PetroChina: A Case Study in Market Structure and Investor Behavior

PetroChina’s A-share initial public offering in 2007 remains one of the most instructive and unforgiving case studies in the interaction between market structure, investor psychology, and regime-dependent valuation in China’s equity markets.

It is not merely a story of a “bad stock” or unfortunate timing; it is a textbook example of how narrative-driven entry, combined with structurally constrained exit, can produce massive and persistent wealth destruction even when the underlying business remains viable.

IPO Mania: Retail Gets the Story Right — and the Timing Wrong

When PetroChina listed on the Shanghai Stock Exchange in November 2007, the context could not have been more euphoric. It was among the largest IPOs globally, raising approximately RMB 66.8 billion (roughly USD 9 billion at the time). Demand was extraordinary. Both institutional and retail tranches were heavily oversubscribed, with retail participation vastly exceeding expectations.

The post-listing price action was explosive. Shares more than doubled shortly after debut, briefly pushing PetroChina’s market capitalization above those of ExxonMobil and other global oil majors. At its peak, PetroChina became the first publicly traded company to surpass a USD 1 trillion market capitalization.

This was classic mainland market behavior at its most extreme:

A national champion narrative tied to China’s industrial ascent and energy security

A state-backed SOE perceived as implicitly protected

A commodity super-cycle reinforcing growth expectations

Immediate price momentum validating the narrative

Retail investors did not misunderstand the story. They misunderstood the price at which the story was being sold. Entry was driven by momentum, visibility, and national pride rather than by valuation discipline or long-term cash-flow realism. This is precisely the environment in which retail capital tends to arrive late —buying not the opportunity, but the confirmation.

The Long Decline: Structural Forces Overwhelm Operating Reality

What followed was not a corporate collapse, accounting scandal, or operational failure. PetroChina remained China’s largest oil and gas producer under CNPC. It generated real revenue, maintained strategic relevance, and continued to operate at scale. Yet over the following decade, its share price entered one of the most prolonged and severe drawdowns in modern equity market history.

From its peak, PetroChina erased hundreds of billions of dollars in market capitalization. Bloomberg and other market observers later described it as the single largest episode of wealth destruction ever recorded in global equity markets.

The drivers were structural, not idiosyncratic:

China’s GDP growth decelerated from investment-heavy double digits toward a more consumption- and services-oriented model

The commodity super-cycle ended, compressing oil price assumptions

Capital markets matured, and policy priorities shifted away from heavy industry

Post-2008 macro tightening reduced tolerance for capital-intensive SOE expansion

None of these forces required PetroChina to fail operationally for equity value to be impaired. They merely required expectations to reset.

Who Absorbed the Downside — and Why

Retail investors who entered during the IPO surge and early post-listing rally found themselves structurally mispositioned. Their entry price implicitly assumed perpetual high growth, sustained commodity tailwinds, and benign policy conditions. When those assumptions unraveled, retail capital proved slow to adapt.

The decline was not sudden enough to force immediate capitulation, nor shallow enough to enable quick recovery. Instead, it was gradual and relentless, the worst possible drawdown profile for any investors. Anchoring bias (“it will come back”), combined with limited portfolio diversification and psychological attachment to the narrative, kept many investors trapped. Selling typically occurred only after prolonged losses, often near cyclical lows.

Institutional investors, by contrast, were not immune to losses, but they were structurally better equipped to manage them. Institutions could:

Size exposure dynamically as oil and macro regimes shifted

Rotate into higher-conviction or less policy-sensitive sectors

Exit incrementally into strength rather than capitulate into weakness

Reallocate capital without emotional or narrative attachment

This asymmetry is not about intelligence or ethics. It is about toolkits, mandates, and time horizons. In China’s policy-influenced markets, those differences matter enormously.

The Behavioral Scar: Lasting Impact on A-Share Market Culture

The PetroChina episode left a deep imprint on China’s onshore investor psyche. It reinforced skepticism toward long-term holding of large SOEs, despite their strategic importance and operational scale. More importantly, it reshaped behavior. Retail investors internalized a lesson — not that PetroChina was overvalued, but that buy-and-hold strategies in China often fail to reward patience, especially when entry is dictated by narrative peaks rather than capital discipline.

The market’s response has been enduring. Preference shifted toward:

Short-cycle trading over long-duration ownership

Policy-endorsed themes over balance-sheet quality

Momentum confirmation over valuation entry

This behavioral legacy continues to shape A-share market dynamics today.

Institutional Interpretation: A Failure of Structure, Not Capitalism

From an institutional perspective, PetroChina was not a failure of state directed capitalism, governance, or even corporate strategy. It was a failure of expectation alignment within a constrained market structure. Retail investors absorbed the downside because they entered at moments of maximum enthusiasm and minimum margin of safety, while institutional capital adjusted exposure as regimes evolved.

The episode illustrates a broader truth about China’s equity markets: downside risk is often socialized through household participation, while upside accrual is episodic, regime-dependent, and frequently captured by capital with greater flexibility and timing advantage. This dynamic, repeated across cycles, underpins the persistent perception, not entirely unfair, that China’s markets are better at distributing risk than compounding wealth.

PetroChina remains the canonical example. Not because it was unique, but because it was large enough, visible enough, and extreme enough to make the structure impossible to ignore.

A Necessary Clarification: Warren Buffett and PetroChina

Any serious discussion of PetroChina must acknowledge a frequently cited counterpoint: Warren Buffett invested in PetroChina and made a substantial profit. This fact is often invoked to argue that PetroChina’s subsequent wealth destruction reflects investor error rather than structural market flaws. That interpretation is incomplete.

Berkshire Hathaway began accumulating PetroChina H-shares in 2002-2003, long before the 2007 A-share IPO and long before PetroChina became a national retail phenomenon. Buffett’s entry occurred at a time when PetroChina traded at a fraction of intrinsic value, priced for deep skepticism around China risk, oil prices, and SOE governance. The investment was fundamentally different in entry point, market venue, and capital structure from what mainland retail investors experienced in 2007.

Equally important, Buffett invested via Hong Kong–listed H-shares, not A-shares. This distinction matters. The H-share market was already institutionally dominated, internationally priced, and unconstrained by the behavioral and mechanical distortions that characterized the A-share IPO frenzy. Buffett was buying PetroChina as a cash-generative oil producer at a depressed valuation, not as a speculative expression of national growth optimism.

Buffett exited the position gradually between 2007 and 2008, near the peak of global commodity optimism and well before the prolonged A-share decline unfolded. In other words, Berkshire’s investment was a classic deep-value, regime-aware trade: buy when expectations were low, sell when narrative and price converged toward optimism. It was not a buy-and-hold endorsement of PetroChina as a perpetual compounder under any policy or macro regime.

This matters because Buffett’s success does not invalidate the PetroChina case study — it reinforces it.

Buffett entered before narrative saturation, not after.

He invested in a different market structure (H-shares vs A-shares).

He exited when valuation normalized, not when retail enthusiasm peaked domestically.

Retail investors in mainland China did the opposite. They encountered PetroChina primarily at the point of maximum visibility and maximum optimism, through a market structure that rewarded momentum and constrained exit. The subsequent wealth destruction was therefore not a contradiction of Buffett’s thesis, but a consequence of radically different entry conditions and structural incentives.

From an institutional perspective, the Buffett example underscores the real lesson of PetroChina: China is investable, but only when valuation, structure, and regime align. Deep value can work. Long-duration narrative buying at policy and sentiment peaks usually does not.

PetroChina did not fail shareholders because it lacked assets or earnings. It failed a generation of retail investors because they were sold duration at a moment when duration was least likely to be rewarded. Buffett’s trade succeeded precisely because it avoided that trap.

This distinction is critical — and too often lost — when PetroChina is cited as either proof of China’s promise or evidence of its dysfunction. It is, in reality, a case study in when, where, and how capital enters the market.

We recommend reading

BRK Daily’s 2023 article on Buffet and PetroChina:

Eagle Point Capital’s 2021 article on Berkshire Hathaway and PetroChina:

Is China Investable? If Yes, Where Alpha Lives

The question of whether China is investable is almost always framed incorrectly. It is not a binary yes-or-no proposition. China is investable but only selectively, episodically, and with a clear appreciation for where alpha can and cannot exist. Investors who approach China as a broad, long-duration value opportunity anchored on headline cheapness tend to be disappointed. Those who treat it as a fragmented opportunity set, governed by distinct market regimes, capital constraints, and policy dynamics, have historically fared far better.

At a high level, alpha in Chinese equities is concentrated rather than diffuse. It does not accrue evenly across the market, nor does it reliably reward passive exposure. Instead, it clusters in specific venues, structures, and time windows, often shaped as much by capital flows and governance regimes as by business fundamentals.

1. Greater China through Hong Kong: The Core Venue for Defensible Exposure

The most durable and institutionally defensible pool of China-related alpha has historically resided in Greater China equities listed offshore, particularly H-shares in Hong Kong. These securities are priced by global capital, traded under internationally legible governance frameworks, and supported by deeper institutional liquidity. While they remain exposed to China-specific regulatory and geopolitical risk, they offer materially better transparency, capital discipline, and exit optionality than onshore markets.

Crucially, Hong Kong-listed equities are more responsive to fundamental analysis. Cash-flow durability, balance-sheet strength, capital allocation discipline, and shareholder return policies carry greater weight in valuation than they do onshore. This does not mean multiples are generous, in fact, persistent discounts are common but it does mean that valuation anchors exist and matter. For long-only capital that insists on some degree of duration and fundamental underwriting, this is the most credible venue for China exposure.

From a portfolio construction perspective, Hong Kong functions as the risk-clearing market for China. It is where global allocators express conviction or reduce exposure when confidence deteriorates. That role often makes Hong Kong equities appear “too cheap” or “too pessimistic,” but it is precisely this pricing discipline that allows selective alpha generation when sentiment and fundamentals realign.

2. Dual-Listed A/H Shares: Structural Relative-Value Alpha

A second, more tactical alpha pocket exists in dual-listed A/H shares, where persistent valuation dislocations reflect segmentation rather than economic reality. The A-share premium and at times discount relative to H-shares is driven by capital controls, investor base differences, liquidity conditions, and sentiment divergence. These gaps are not static. They widen and compress as policy tone, cross-border flows, and risk appetite shift.

For disciplined investors focused on relative value rather than narrative, AH premium mean reversion has been one of the more repeatable sources of China-related alpha. Importantly, this is not a buy-and-hold trade. It requires active monitoring of flows, policy signals, and positioning. The opportunity lies in exploiting structural inefficiency, not forecasting long-term growth.

3. Sector Selectivity Over Country Allocation

Beyond market structure, sector selection matters far more than broad country exposure. Certain niches retain secular growth drivers that are less dependent on short-term macro stimulus or heavy industrial cycles. These include select platform technology businesses, consumer franchises with genuine pricing power, and infrastructure-adjacent digital or services platforms embedded in long-term policy priorities.

These opportunities are most effectively accessed via Hong Kong listings or US ADRs, where disclosure standards are higher, corporate governance is more scrutinized, and capital allocation decisions face external discipline. Even within these sectors, alpha accrual is uneven. Regulatory cycles, data governance concerns, and shifting policy priorities can interrupt compounding abruptly. As such, position sizing, valuation discipline, and predefined exit criteria are essential.

4. Macro-Risk Arbitrage: Trading Policy Inflections

Another important, though frequently misunderstood source of returns in China is macro-risk arbitrage tied to policy inflection points. Chinese markets remain uniquely sensitive to changes in regulatory tone, fiscal stance, and capital-flow management. Short bursts of performance are often driven less by earnings revisions and more by shifts in perceived policy tolerance.

These windows can be profitable, particularly for hedge funds and active traders, but they are inherently short-lived and reflexive. They are unsuitable for passive exposure or long-duration underwriting. Investors operating in this space must be willing to trade around positions aggressively, harvest gains quickly, and accept that policy-driven rallies often lack follow-through absent a broader confidence reset.

5. Onshore A-Shares: A Tactical Market, Not a Compounding One

By contrast, onshore A-shares should be treated primarily as a tactical market, not a compounding one. Opportunities certainly exist, particularly around policy-favored themes, liquidity injections, and sentiment-driven momentum, but extracting alpha requires an explicitly short-term orientation. Market mechanics such as retail dominance, price limits, T+1 settlement, and rapid narrative rotation all work against patient capital.

Passive exposure to A-shares is effectively a bet on regime stability and sentiment persistence, two conditions that have historically been transient. For most institutional portfolios, A-shares are better suited as a tactical overlay rather than a core allocation.

Bottom Line

China is investable, but not indiscriminately. Alpha lives where structure, incentives, and time horizon align. It is most defensible offshore, episodic in relative-value trades, and tactical in policy-driven windows. Investors who insist on treating China as a conventional emerging-market value play will likely remain frustrated. Those who respect its fragmentation, trade its regimes, and size their exposure accordingly can still generate meaningful returns.

How to Extract Alpha and Translate It into Portfolio Performance

Extracting alpha in China and Greater China is not about being early to a macro recovery, nor about buying statistical cheapness and waiting for convergence. Those approaches assume a market structure that rewards patience, duration, and linear fundamental realization. China does not operate that way. Alpha is generated by structuring exposure correctly, understanding who sets prices, and trading within policy-driven regimes rather than fighting them.

The defining mistake global investors make is not misreading China’s fundamentals, it is misaligning capital with the market’s payoff function.

1. Structure Exposure by Market Regime, Not by Geography

China should never be treated as a single allocation bucket. Market venue determines behavior, liquidity, and return distribution far more than domicile.

Hong Kong–listed H-shares are the only credible venue for long-duration China exposure. Capital is globally priced, liquidity is institutionally dominated, and governance, while imperfect, it is at least interpretable within international norms. Disclosure, settlement, currency convertibility, and exit mechanics align with global portfolio requirements. If China is to generate multi-year compounding for foreign capital, it will occur through offshore listings where investors retain exit optionality and currency transparency.

This does not imply low risk. It implies knowable risk.

Mainland A-shares, by contrast, are best understood as tactical instruments. Price action responds disproportionately to policy signaling, liquidity injections, sector rotation, and narrative momentum rather than discounted cash flows. Market mechanics, such as retail participation, price limits, T+1 settlement, and constrained shorting, structurally favor timing over duration. These markets reward speed, flexibility, and regime awareness, not patience. Capital allocated here should be sized with the explicit intent to trade rather than to own.

The most common error is deploying long-term capital into short-horizon markets and then attributing the resulting drawdowns to “China risk” rather than to structural mismatch.

2. Use Quant Filters to Identify Structural Mispricings

In China, alpha is rarely found in absolute valuation metrics viewed in isolation. It emerges from relative dislocations created by segmentation, not from static notions of cheapness.

The most repeatable opportunities include:

AH premium and discount spreads, which frequently widen beyond fundamental justification during risk-off episodes and compress rapidly during liquidity or policy reversals. These moves are driven by flow mechanics and investor base differences, not changes in intrinsic value.

Cross-listed relative value, where economically identical businesses trade at materially different multiples due to capital access, index inclusion, liquidity depth, or sentiment divergence.

GARP versus deep-value distortions, particularly in policy-favored sectors where growth optics attract capital despite deteriorating balance-sheet quality, while cash-generative but unfashionable businesses are neglected.

These are not buy-and-hold investments. They are mean-reversion trades. Success depends on disciplined entry, explicit exit rules, and position sizing that assumes volatility rather than hopes it away.

3. Respect Market Structure More Than Macro Narratives

Headline GDP growth, five-year plans, and stimulus announcements are consistently over-weighted in China equity narratives. In practice, they matter far less than who is trading, with what liquidity, and under which constraints.

Chinese equity markets are fundamentally flow-driven:

Institutional re-risking and de-risking determines inflection points.

Retail participation amplifies momentum late in cycles rather than initiating it.

Liquidity availability, not earnings revisions, dominates short-term price discovery.

Markets can and often do move sharply in the absence of new fundamental information. Ignoring market structure is how fundamentally “correct” theses lose money, repeatedly and predictably.

4. Trade Policy Signals, Don’t Underwrite Them

Policy in China should not be treated as a long-term guarantee. It is a short-term catalyst.

Regulatory pivots, sector endorsements, fiscal announcements, and verbal guidance reliably produce sharp rallies. The mistake investors make is extrapolating these moves into durable re-ratings. Policy support in China is frequently tactical, conditional, and reversible. Alpha is generated by trading around policy volatility, not by assuming policy permanence.

The objective is not to forecast policy success. It is to monetize the price volatility created by policy uncertainty. Investors who attempt to underwrite policy credibility as a substitute for fundamentals often discover that credibility has a shorter half-life than their holding period.

5. Risk Control Is Non-Negotiable

China carries systemic regime risk that cannot be diversified away through sector selection or security count. These risks include:

Sudden regulatory intervention

Capital-flow interruptions

Liquidity air pockets

Policy reversals without warning

They are infrequent, but when they occur, they dominate returns and overwhelm traditional risk models.

As a result, risk management is alpha. Position sizing, liquidity awareness, jurisdictional exposure limits, and explicit downside rules are not optional overlays, they are core inputs. Volatility itself is not the primary risk. The true risk is the inability to transact when regimes shift.

Bottom Line

Alpha in China does not come from conviction alone. It comes from alignmen between capital, structure, and time horizon. Investors who treat China as a conventional emerging-market value opportunity will continue to struggle. Those who segment markets correctly, exploit structural dislocations, trade policy regimes rather than worship them, and prioritize risk control can still translate China exposure into portfolio performance.

In China, alpha is not about being right. It is about being positioned correctly when the market decides who gets paid.

Conclusion: China Is Not Broken — It Is Structured Differently

China’s equity markets are not irrational, broken, or uninvestable. They are structurally different, and those differences determine who gets paid, when, and for how long. The persistent frustration global investors experience does not stem from a failure of growth or a lack of opportunity, but from a mismatch between capital expectations and market design.

China is not a market that reliably rewards passive exposure, linear fundamental extrapolation, or blind faith in statistical cheapness. It is a regime-driven system where policy, liquidity, and market structure compress duration and elevate timing. In such an environment, valuation is real but conditional; fundamentals matter, but unevenly; and patience is rewarded only when aligned with the prevailing regime.

The distinction between mainland A-shares and offshore H-shares is central, not academic. These are not interchangeable expressions of “China exposure,” but separate asset classes with different investor bases, mechanics, and payoff functions. Hong Kong prices China risk through a global lens and offers the only defensible venue for long-duration exposure. Mainland markets, by contrast, function as tactical arenas where alpha is episodic and flow-driven.

Episodes like PetroChina are not anomalies. They are structural case studies in how narrative peaks, constrained exits, and regime shifts transfer risk from institutions to households and why retail behavior, policy signaling, and market mechanics cannot be ignored. Even Warren Buffett’s success in PetroChina reinforces the point: when, where, and how capital enters China matters more than the story itself.

The implication is clear. China remains investable, but only for investors willing to abandon simplistic frameworks and engage with the market on its own terms. Alpha lives in segmentation, relative value, policy-driven windows, and disciplined risk control, not in broad “cheap China” narratives.

For those prepared to respect structure, size risk appropriately, and trade regimes rather than fight them, China can still contribute meaningfully to portfolio performance. For those who insist on treating it like a conventional emerging market, disappointment is not a possibility, it is the base case.

In China, returns are not denied. They are conditional.

Disclaimer, Disclosure, Conflicts & Copyright Notice

This publication has been prepared solely for informational and educational purposes by Alpha Talon Investment Research (“Alpha Talon”). The views expressed herein represent the author’s independent analysis and opinions as of the date of writing and may change without notice. This material does not constitute investment advice, financial advice, legal advice, tax advice, or a recommendation to buy, sell, or hold any security, derivative, or financial instrument. Nothing contained in this document should be construed as an offer to sell or a solicitation to buy any securities.

Investing in securities involves significant risk, including the possible loss of principal. Equity investments may fluctuate in price, sometimes dramatically. Securities in the biotechnology, pharmaceutical, oncology, and healthcare sectors, such as those discussed herein are subject to heightened levels of clinical, regulatory, competitive, and operational risk. Forward-looking statements, projections, price targets, valuation scenarios, and estimates included in this report are inherently speculative, based on numerous assumptions, and may differ materially from actual outcomes. Past performance is not indicative of future results.

This material has not been prepared in accordance with the legal requirements designed to promote the independence of investment research produced by broker-dealers or regulated financial institutions. This document is not a research report under FINRA, SEC, FCA, or MiFID II definitions. It has not been reviewed, endorsed, or approved by any regulatory authority, including FINRA, the SEC, or any similar body. Alpha Talon is not a registered investment adviser, broker-dealer, or financial institution under SFC or MPFA.

Readers should conduct independent research and due diligence before making any investment decision. You should consult a licensed investment adviser, registered financial professional, tax specialist, or attorney regarding your specific financial situation and risk tolerance. Nothing in this publication establishes any fiduciary relationship, advisory relationship, or obligation on the part of the author or Alpha Talon toward any reader.

The author and affiliated accounts may hold long or short positions in the securities and financial instruments discussed in this report and may trade in them before, during, or after publication without further notice. These positions may be contrary to the views expressed herein. The author does not receive compensation from the issuers of any securities mentioned. Alpha Talon does not have investment banking relationships, commercial relationships, consulting arrangements, or compensation agreements with the companies discussed in this document.

No part of the author’s compensation is directly or indirectly related to the specific recommendations, analyses, or opinions expressed in this report.

All investments involve risk, including loss of principal. Certain securities discussed may be speculative or volatile and may not be suitable for all investors. Clinical trial failures, regulatory decisions, market conditions, macroeconomic shifts, geopolitical developments, and competitive pressures can significantly impact the securities analyzed. This information is provided “as is,” without warranty of any kind, express or implied.

Securities mentioned herein are not guaranteed, not insured, and not protected by SIPC except as applicable for brokerage custody, and are not obligations of, or guaranteed by, any bank or government agency.

Alpha Talon, its author(s), and affiliates expressly disclaim all liability for errors, omissions, or any direct, indirect, incidental, or consequential losses arising from the use of this material. Use of the information is at the reader’s sole risk.

This material may not be distributed or used in any jurisdiction where such use or distribution would be contrary to local law or regulation. Readers are responsible for complying with applicable securities laws.